Introduction

Benign neoplasms of the female genital tract refer to non-cancerous growths that can occur in various parts of the reproductive system, including the uterus, ovaries, cervix, and vagina[1][2]. These growths are usually not life-threatening but can cause symptoms and complications[3]. The aim of this guide is to provide a comprehensive overview of the diagnosis and management of benign neoplasms of the female genital tract.

Codes

- ICPC-2 Code: X80 Benign neoplasm female genital[4]

- ICD-10 Code: D28.9 Benign neoplasm of female genital organ, unspecified[5]

Symptoms

- Abnormal vaginal bleeding: This can include heavy or prolonged menstrual bleeding, bleeding between periods, or postmenopausal bleeding[6].

- Pelvic pain or pressure: Some women may experience pain or discomfort in the pelvic region, which can be constant or intermittent[7].

- Abnormal vaginal discharge: A benign neoplasm may cause changes in vaginal discharge, such as an increase in volume or an unusual odor[8].

- Urinary symptoms: In some cases, a benign neoplasm may press on the bladder or urethra, leading to urinary frequency, urgency, or difficulty emptying the bladder[9].

- Bowel symptoms: If a benign neoplasm affects the rectum or colon, it may cause symptoms such as constipation, diarrhea, or rectal bleeding[10]..

Causes

The exact causes of benign neoplasms of the female genital tract are not fully understood. However, several factors may contribute to their development, including:

- Hormonal imbalances: Fluctuations in hormone levels, particularly estrogen and progesterone, may play a role in the development of certain types of benign neoplasms[11].

- Genetic factors: Some benign neoplasms may have a genetic component, meaning that individuals with a family history of these growths may be at a higher risk[12].

- Chronic inflammation: Chronic inflammation in the reproductive organs, such as chronic pelvic inflammatory disease, may increase the risk of developing benign neoplasms[13].

- Environmental factors: Exposure to certain chemicals or toxins may increase the risk of developing benign neoplasms[14].

Diagnostic Steps

Medical History

A comprehensive medical history should be obtained to gather relevant patient information. Key points to consider include:

- Menstrual history: The pattern and regularity of menstrual cycles, as well as any changes in bleeding patterns, should be assessed[15].

- Symptoms: The presence and characteristics of symptoms, such as abnormal vaginal bleeding, pelvic pain, or urinary/bowel symptoms, should be documented[16].

- Risk factors: Any known risk factors for benign neoplasms, such as a family history of these growths or a history of hormonal imbalances, should be identified[17].

- Medical conditions: The presence of any underlying medical conditions, such as polycystic ovary syndrome or endometriosis, should be noted[18].

Physical Examination

A thorough physical examination should be performed, focusing on specific signs or findings indicative of benign neoplasms. Key points to consider include:

- Pelvic examination: A pelvic examination allows the healthcare provider to assess the size, shape, and consistency of the reproductive organs. Any palpable masses or abnormalities should be noted[19].

- Speculum examination: A speculum examination is performed to visualize the cervix and vagina. Any visible abnormalities, such as growths or lesions, should be documented[20].

- Digital rectal examination: In some cases, a digital rectal examination may be performed to assess the rectum and surrounding structures for any abnormalities[21].

Laboratory Tests

Laboratory tests may be used to aid in the diagnosis of benign neoplasms of the female genital tract. These tests may include:

- Complete blood count (CBC): A CBC can help assess for anemia or other blood abnormalities that may be associated with benign neoplasms[22].

- Hormone levels: Hormone levels, such as estrogen and progesterone, may be measured to evaluate for hormonal imbalances that could contribute to the development of benign neoplasms[23].

- Tumor markers: In some cases, specific tumor markers, such as CA-125, may be measured to assess for the presence of certain types of benign neoplasms[24].

Diagnostic Imaging

Diagnostic imaging modalities may be used to visualize and assess benign neoplasms of the female genital tract. These may include:

- Transvaginal ultrasound: This imaging technique uses sound waves to create images of the reproductive organs. It can help assess the size, location, and characteristics of benign neoplasms[25].

- Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI): MRI provides detailed images of the reproductive organs and can help differentiate between benign neoplasms and other conditions[26].

- Computed tomography (CT) scan: CT scans may be used to evaluate the extent of a benign neoplasm and its relationship to surrounding structures[27].

Other Tests

Additional diagnostic tests or procedures may be necessary based on the clinical presentation. These may include:

- Endometrial biopsy: If abnormal vaginal bleeding is present, an endometrial biopsy may be performed to assess the lining of the uterus for any abnormalities[28].

- Colposcopy: Colposcopy involves using a specialized instrument to examine the cervix and vagina in more detail. It can help identify any abnormal areas that may require further evaluation[29].

- Hysteroscopy: Hysteroscopy involves inserting a thin, lighted tube into the uterus to visualize the uterine cavity. It can help identify any abnormalities, such as polyps or fibroids[30].

Follow-up and Patient Education

After the diagnostic evaluation, appropriate follow-up and patient education should be provided. This may include:

- Discussion of the diagnosis: The healthcare provider should explain the diagnosis of a benign neoplasm and provide information about the specific type, location, and potential complications[31].

- Treatment options: The available treatment options should be discussed, including both traditional interventions and alternative interventions[32].

- Monitoring and follow-up: The patient should be informed about the need for regular monitoring and follow-up appointments to assess the growth and any changes in symptoms[33].

- Emotional support: The patient may require emotional support and counseling to cope with the diagnosis and any associated anxiety or concerns[34].

Possible Interventions

Traditional Interventions

Medications:

Top 5 drugs for Benign neoplasm female genital:

- Oral contraceptives (e.g., Ethinyl estradiol and norethindrone)[35]:

- Cost: Generic versions can be $10-$50/month[36].

- Contraindications: History of blood clots, liver disease, certain types of cancer[35].

- Side effects: Nausea, breast tenderness, breakthrough bleeding[35].

- Severe side effects: Blood clots, stroke, heart attack[35].

- Drug interactions: Certain antibiotics, anticonvulsants[37].

- Warning: Increased risk of blood clots in women over 35 who smoke[35].

- Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) (e.g., Ibuprofen, Naproxen)[38]:

- Cost: Generic versions are typically <$10/month[39].

- Contraindications: History of stomach ulcers, kidney disease, bleeding disorders[38].

- Side effects: Upset stomach, heartburn, increased risk of bleeding[38].

- Severe side effects: Stomach ulcers, kidney problems, allergic reactions[38].

- Drug interactions: Blood thinners, certain antidepressants[40].

- Warning: Prolonged use can increase the risk of heart attack or stroke[38].

- Gonadotropin-releasing hormone (GnRH) agonists (e.g., Leuprolide)[41]:

- Cost: $300-$800/month[42].

- Contraindications: Pregnancy, breastfeeding, undiagnosed vaginal bleeding[41].

- Side effects: Hot flashes, mood swings, vaginal dryness[41].

- Severe side effects: Osteoporosis, increased risk of fractures[41].

- Drug interactions: None reported[41].

- Warning: Long-term use may lead to bone loss[41].

- Progestin therapy (e.g., Medroxyprogesterone acetate)[43]:

- Cost: Generic versions can be $10-$50/month[44].

- Contraindications: History of blood clots, liver disease, certain types of cancer[43].

- Side effects: Irregular bleeding, weight gain, mood changes[43].

- Severe side effects: Blood clots, stroke, heart attack[43].

- Drug interactions: Certain antibiotics, anticonvulsants[45].

- Warning: Increased risk of blood clots in women over 35 who smoke[43].

- Selective estrogen receptor modulators (SERMs) (e.g., Tamoxifen)[46]:

- Cost: $50-$200/month[47].

- Contraindications: History of blood clots, certain types of cancer[46].

- Side effects: Hot flashes, vaginal dryness, increased risk of uterine cancer[46].

- Severe side effects: Blood clots, stroke, endometrial cancer[46].

- Drug interactions: Certain antidepressants, blood thinners[48].

- Warning: Increased risk of uterine cancer with long-term use[46].

Alternative Drugs:

- Danazol: A synthetic androgen that can help reduce the size of benign neoplasms[49].

- Aromatase inhibitors: These medications block the production of estrogen and may be used in certain cases[50].

- Mifepristone: A progesterone receptor antagonist that can be used to treat certain types of benign neoplasms[51].

- Gonadotropin-releasing hormone (GnRH) antagonists: These medications block the action of GnRH and can help shrink benign neoplasms[52].

- Anti-androgens: These medications can help reduce the size of benign neoplasms that are hormone-sensitive[53].

Surgical Procedures:

- Hysterectomy: Surgical removal of the uterus. Cost: $10,000 to $20,000[54].

- Myomectomy: Surgical removal of fibroids while preserving the uterus. Cost: $5,000 to $15,000[55].

- Oophorectomy: Surgical removal of one or both ovaries. Cost: $5,000 to $15,000[56].

- Cervical conization: Surgical removal of a cone-shaped piece of tissue from the cervix. Cost: $3,000 to $8,000[57].

- Excisional biopsy: Surgical removal of a suspicious growth or lesion for further evaluation. Cost: $1,000 to $5,000[58].

Alternative Interventions

- Herbal supplements: Some herbal supplements, such as green tea extract or turmeric, may have potential benefits for reducing the size of benign neoplasms. Cost: Varies depending on the specific supplement[59].

- Acupuncture: Acupuncture may help reduce pain and improve overall well-being. Cost: $60-$120 per session[60].

- Mind-body techniques: Techniques such as meditation, yoga, or relaxation exercises may help manage symptoms and improve quality of life. Cost: Varies depending on the specific program or class[61].

- Dietary modifications: A healthy diet rich in fruits, vegetables, and whole grains may help support overall health and reduce the risk of complications. Cost: Varies depending on individual food choices[62].

- Physical therapy: Pelvic floor physical therapy may help manage pelvic pain and improve pelvic muscle function. Cost: $100-$200 per session[63].

Lifestyle Interventions

- Regular exercise: Engaging in regular physical activity, such as walking, swimming, or cycling, can help improve overall health and well-being. Cost: Varies depending on individual preferences (e.g., gym membership, equipment costs)[64].

- Healthy diet: Following a balanced diet that includes a variety of nutrient-rich foods can support overall health and may help reduce the risk of complications. Cost: Varies depending on individual food choices[65].

- Stress management: Engaging in stress-reducing activities, such as meditation, deep breathing exercises, or hobbies, can help improve overall well-being. Cost: Varies depending on individual preferences (e.g., meditation app subscription, hobby supplies)[66].

- Smoking cessation: Quitting smoking can have significant positive effects on both short- and long-term health, reducing the risk of chronic diseases such as heart disease, stroke, and cancer. Cost: May vary depending on the method used (e.g., nicotine replacement therapy, counseling services)[67].

Mirari Cold Plasma Alternative Intervention

Understanding Mirari Cold Plasma

- Safe and Non-Invasive Treatment: Mirari Cold Plasma is a safe and non-invasive treatment option for various skin conditions. It does not require incisions, minimizing the risk of scarring, bleeding, or tissue damage.

- Efficient Extraction of Foreign Bodies: Mirari Cold Plasma facilitates the removal of foreign bodies from the skin by degrading and dissociating organic matter, allowing easier access and extraction.

- Pain Reduction and Comfort: Mirari Cold Plasma has a local analgesic effect, providing pain relief during the treatment, making it more comfortable for the patient.

- Reduced Risk of Infection: Mirari Cold Plasma has antimicrobial properties, effectively killing bacteria and reducing the risk of infection.

- Accelerated Healing and Minimal Scarring: Mirari Cold Plasma stimulates wound healing and tissue regeneration, reducing healing time and minimizing the formation of scars.

Mirari Cold Plasma Prescription

Video instructions for using Mirari Cold Plasma Device – X80 Benign neoplasm female genital (ICD-10:D28.9)

| Mild | Moderate | Severe |

| Mode setting: 1 (Infection) Location: 0 (Localized) Morning: 15 minutes, Evening: 15 minutes |

Mode setting: 1 (Infection) Location: 0 (Localized) Morning: 30 minutes, Lunch: 30 minutes, Evening: 30 minutes |

Mode setting: 1 (Infection) Location: 0 (Localized) Morning: 30 minutes, Lunch: 30 minutes, Evening: 30 minutes |

| Mode setting: 2 (Wound Healing) Location: 0 (Localized) Morning: 15 minutes, Evening: 15 minutes |

Mode setting: 2 (Wound Healing) Location: 0 (Localized) Morning: 30 minutes, Lunch: 30 minutes, Evening: 30 minutes |

Mode setting: 2 (Wound Healing) Location: 0 (Localized) Morning: 30 minutes, Lunch: 30 minutes, Evening: 30 minutes |

| Mode setting: 3 (Antiviral Therapy) Location: 0 (Localized) Morning: 15 minutes, Evening: 15 minutes |

Mode setting: 3 (Antiviral Therapy) Location: 0 (Localized) Morning: 30 minutes, Lunch: 30 minutes, Evening: 30 minutes |

Mode setting: 3 (Antiviral Therapy) Location: 0 (Localized) Morning: 30 minutes, Lunch: 30 minutes, Evening: 30 minutes |

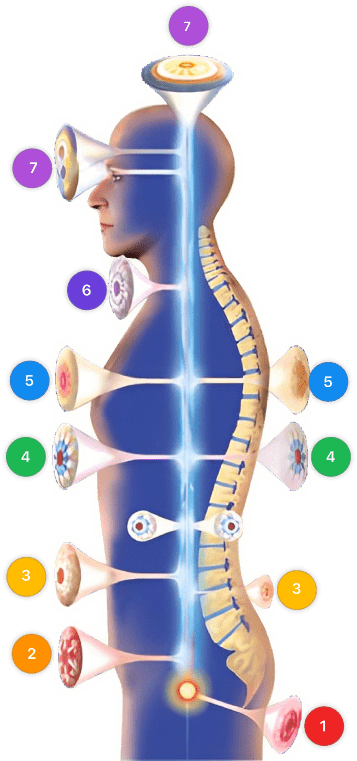

| Mode setting: 7 (Immunotherapy) Location: 1 (Sacrum) Morning: 15 minutes, Evening: 15 minutes |

Mode setting: 7 (Immunotherapy) Location: 1 (Sacrum) Morning: 30 minutes, Lunch: 30 minutes, Evening: 30 minutes |

Mode setting: 7 (Immunotherapy) Location: 1 (Sacrum) Morning: 30 minutes, Lunch: 30 minutes, Evening: 30 minutes |

| Total Morning: 60 minutes approx. $10 USD, Evening: 60 minutes approx. $10 USD |

Total Morning: 120 minutes approx. $20 USD, Lunch: 120 minutes approx. $20 USD, Evening: 120 minutes approx. $20 USD, |

Total Morning: 120 minutes approx. $20 USD, Lunch: 120 minutes approx. $20 USD, Evening: 120 minutes approx. $20 USD, |

| Usual treatment for 7-60 days approx. $140 USD – $1200 USD | Usual treatment for 6-8 weeks approx. $2,520 USD – $3,360 USD |

Usual treatment for 3-6 months approx. $5,400 USD – $10,800 USD

|

|

|

Use the Mirari Cold Plasma device to treat Benign neoplasm female genital effectively.

WARNING: MIRARI COLD PLASMA IS DESIGNED FOR THE HUMAN BODY WITHOUT ANY ARTIFICIAL OR THIRD PARTY PRODUCTS. USE OF OTHER PRODUCTS IN COMBINATION WITH MIRARI COLD PLASMA MAY CAUSE UNPREDICTABLE EFFECTS, HARM OR INJURY. PLEASE CONSULT A MEDICAL PROFESSIONAL BEFORE COMBINING ANY OTHER PRODUCTS WITH USE OF MIRARI.

Step 1: Cleanse the Skin

- Start by cleaning the affected area of the skin with a gentle cleanser or mild soap and water. Gently pat the area dry with a clean towel.

Step 2: Prepare the Mirari Cold Plasma device

- Ensure that the Mirari Cold Plasma device is fully charged or has fresh batteries as per the manufacturer’s instructions. Make sure the device is clean and in good working condition.

- Switch on the Mirari device using the power button or by following the specific instructions provided with the device.

- Some Mirari devices may have adjustable settings for intensity or treatment duration. Follow the manufacturer’s instructions to select the appropriate settings based on your needs and the recommended guidelines.

Step 3: Apply the Device

- Place the Mirari device in direct contact with the affected area of the skin. Gently glide or hold the device over the skin surface, ensuring even coverage of the area experiencing.

- Slowly move the Mirari device in a circular motion or follow a specific pattern as indicated in the user manual. This helps ensure thorough treatment coverage.

Step 4: Monitor and Assess:

- Keep track of your progress and evaluate the effectiveness of the Mirari device in managing your Benign neoplasm female genital. If you have any concerns or notice any adverse reactions, consult with your health care professional.

Note

This guide is for informational purposes only and should not replace the advice of a medical professional. Always consult with your healthcare provider or a qualified medical professional for personal advice, diagnosis, or treatment. Do not solely rely on the information presented here for decisions about your health. Use of this information is at your own risk. The authors of this guide, nor any associated entities or platforms, are not responsible for any potential adverse effects or outcomes based on the content.

Mirari Cold Plasma System Disclaimer

- Purpose: The Mirari Cold Plasma System is a Class 2 medical device designed for use by trained healthcare professionals. It is registered for use in Thailand and Vietnam. It is not intended for use outside of these locations.

- Informational Use: The content and information provided with the device are for educational and informational purposes only. They are not a substitute for professional medical advice or care.

- Variable Outcomes: While the device is approved for specific uses, individual outcomes can differ. We do not assert or guarantee specific medical outcomes.

- Consultation: Prior to utilizing the device or making decisions based on its content, it is essential to consult with a Certified Mirari Tele-Therapist and your medical healthcare provider regarding specific protocols.

- Liability: By using this device, users are acknowledging and accepting all potential risks. Neither the manufacturer nor the distributor will be held accountable for any adverse reactions, injuries, or damages stemming from its use.

- Geographical Availability: This device has received approval for designated purposes by the Thai and Vietnam FDA. As of now, outside of Thailand and Vietnam, the Mirari Cold Plasma System is not available for purchase or use.

References

- Stewart, E. A., Cookson, C. L., Gandolfo, R. A., & Schulze-Rath, R. (2017). Epidemiology of uterine fibroids: a systematic review. BJOG: An International Journal of Obstetrics & Gynaecology, 124(10), 1501-1512. https://doi.org/10.1111/1471-0528.14640

- Kurman, R. J., Carcangiu, M. L., Herrington, C. S., & Young, R. H. (Eds.). (2014). WHO classification of tumours of female reproductive organs. International Agency for Research on Cancer.

- Levy, G., Hill, M. J., Beall, S., Zarek, S. M., Segars, J. H., & Catherino, W. H. (2012). Leiomyoma: genetics, assisted reproduction, pregnancy and therapeutic advances. Journal of Assisted Reproduction and Genetics, 29(8), 703-712. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10815-012-9784-0

- International Classification of Primary Care – PH3C. ICPC-2 Code: X80 Benign neoplasm female genital. http://www.ph3c.org/PH3C/docs/27/000496/0000908.pdf

- World Health Organization. (2023). ICD-10 Code: D28.9 Benign neoplasm of female genital organ, unspecified. https://icd.who.int/browse10/2019/en#/D28.9

- American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. (2021). Abnormal Uterine Bleeding. https://www.acog.org/womens-health/faqs/abnormal-uterine-bleeding

- Gouri, A., Polubothu, S., & Curry, J. I. (2019). Pelvic pain in girls and women. The Obstetrician & Gynaecologist, 21(2), 87-95. https://doi.org/10.1111/tog.12567

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2022). Vaginal Discharge. https://www.cdc.gov/std/treatment-guidelines/vaginal-discharge.htm

- Fakhoury, M., & Radfar, L. (2022). Uterine Leiomyoma. In StatPearls. StatPearls Publishing. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK562304/

- Rana, S. V., & Malik, A. (2014). Functional Gastrointestinal Disorders in Gynecological Practice. Journal of Mid-life Health, 5(2), 57-61. https://doi.org/10.4103/0976-7800.133986

- Maruo, T., Ohara, N., Wang, J., & Matsuo, H. (2004). Sex steroidal regulation of uterine leiomyoma growth and apoptosis. Human Reproduction Update, 10(3), 207-220. https://doi.org/10.1093/humupd/dmh019

- Wellons, M. F., Lewis, C. E., Schwartz, S. M., Gunderson, E. P., Schreiner, P. J., Sternfeld, B., … & Siscovick, D. S. (2008). Racial differences in self-reported infertility and risk factors for infertility in a cohort of black and white women: the CARDIA Women’s Study. Fertility and Sterility, 90(5), 1640-1648. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.fertnstert.2007.09.056

- Vercellini, P., Viganò, P., Somigliana, E., & Fedele, L. (2014). Endometriosis: pathogenesis and treatment. Nature Reviews Endocrinology, 10(5), 261-275. https://doi.org/10.1038/nrendo.2013.255

- Weuve, J., Hauser, R., Calafat, A. M., Missmer, S. A., & Wise, L. A. (2010). Association of exposure to phthalates with endometriosis and uterine leiomyomata: findings from NHANES, 1999–2004. Environmental Health Perspectives, 118(6), 825-832. https://doi.org/10.1289/ehp.0901543

- The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. (2023). Abnormal Uterine Bleeding. https://www.acog.org/womens-health/faqs/abnormal-uterine-bleeding

- Munro, M. G., Critchley, H. O., Broder, M. S., & Fraser, I. S. (2011). FIGO classification system (PALM-COEIN) for causes of abnormal uterine bleeding in nongravid women of reproductive age. International Journal of Gynecology & Obstetrics, 113(1), 3-13. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijgo.2010.11.011

- Stewart, E. A., Laughlin-Tommaso, S. K., Catherino, W. H., Lalitkumar, S., Gupta, D., & Vollenhoven, B. (2016). Uterine fibroids. Nature Reviews Disease Primers, 2, 16043. https://doi.org/10.1038/nrdp.2016.43

- Legro, R. S., Arslanian, S. A., Ehrmann, D. A., Hoeger, K. M., Murad, M. H., Pasquali, R., & Welt, C. K. (2013). Diagnosis and treatment of polycystic ovary syndrome: an Endocrine Society clinical practice guideline. The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism, 98(12), 4565-4592. https://doi.org/10.1210/jc.2013-2350

- Bates, C. K., Carroll, N., & Potter, J. (2011). The challenging pelvic examination. Journal of General Internal Medicine, 26(6), 651-657. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-010-1610-8

- American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. (2020). Well-Woman Visit. https://www.acog.org/clinical/clinical-guidance/committee-opinion/articles/2018/10/well-woman-visit

- Talley, N. J., & O’Connor, S. (2018). Clinical Examination: A Systematic Guide to Physical Diagnosis (8th ed.). Elsevier.

- Hoffman, B. L., Schorge, J. O., Bradshaw, K. D., Halvorson, L. M., Schaffer, J. I., & Corton, M. M. (2020). Williams Gynecology (4th ed.). McGraw-Hill Education.

- Bulun, S. E. (2013). Uterine fibroids. New England Journal of Medicine, 369(14), 1344-1355. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMra1209993

- Sölétormos, G., Duffy, M. J., Othman Abu Hassan, S., Verheijen, R. H., Tholander, B., Bast, R. C., Jr, … & Molina, R. (2016). Clinical Use of Cancer Biomarkers in Epithelial Ovarian Cancer: Updated Guidelines From the European Group on Tumor Markers. International Journal of Gynecological Cancer, 26(1), 43-51. https://doi.org/10.1097/IGC.0000000000000586

- Levine, D., Brown, D. L., Andreotti, R. F., Benacerraf, B., Benson, C. B., Brewster, W. R., … & Frates, M. C. (2010). Management of asymptomatic ovarian and other adnexal cysts imaged at US: Society of Radiologists in Ultrasound Consensus Conference Statement. Radiology, 256(3), 943-954. https://doi.org/10.1148/radiol.10100213

- Siegelman, E. S., & Outwater, E. K. (1999). MR Imaging of the Ovary and Adnexa. Radiology, 210(3), 610-618. https://doi.org/10.1148/radiology.212.1.r99jl455

- Iyer, V. R., & Lee, S. I. (2010). MRI, CT, and PET/CT for ovarian cancer detection and adnexal lesion characterization. American Journal of Roentgenology, 194(2), 311-321. https://doi.org/10.2214/AJR.09.3522

- American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. (2018). The Role of Transvaginal Ultrasonography in Evaluating the Endometrium of Women With Postmenopausal Bleeding. ACOG Committee Opinion No. 734. Obstetrics & Gynecology, 131(5), e124-e129. https://doi.org/10.1097/AOG.0000000000002631

- Massad, L. S., Einstein, M. H., Huh, W. K., Katki, H. A., Kinney, W. K., Schiffman, M., Solomon, D., Wentzensen, N., & Lawson, H. W. (2013). 2012 Updated Consensus Guidelines for the Management of Abnormal Cervical Cancer Screening Tests and Cancer Precursors. Journal of Lower Genital Tract Disease, 17(5 Suppl 1), S1-S27. https://doi.org/10.1097/lgt.0b013e318287d329

- Di Spiezio Sardo, A., Calagna, G., Santangelo, F., Zizolfi, B., Tanos, V., Perino, A., & De Wilde, R. L. (2017). The Role of Hysteroscopy in the Diagnosis and Treatment of Adenomyosis. BioMed Research International, 2017, 2518396. https://doi.org/10.1155/2017/2518396

- Vilos, G. A., Allaire, C., Laberge, P. Y., Leyland, N., Special Contributors, Vilos, A. G., … & Chen, I. (2015). The management of uterine leiomyomas. Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology Canada, 37(2), 157-178. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1701-2163(15)30338-8

- Lumsden, M. A., Hamoodi, I., Gupta, J., & Hickey, M. (2015). Fibroids: diagnosis and management. BMJ, 351, h4887. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.h4887

- Wallach, E. E., & Vlahos, N. F. (2004). Uterine myomas: an overview of development, clinical features, and management. Obstetrics & Gynecology, 104(2), 393-406. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.AOG.0000136079.62513.39

- Borah, B. J., Nicholson, W. K., Bradley, L., & Stewart, E. A. (2013). The impact of uterine leiomyomas: a national survey of affected women. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology, 209(4), 319.e1-319.e20. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajog.2013.07.017

- The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. (2022). Combined Hormonal Birth Control: Pill, Patch, and Ring. https://www.acog.org/womens-health/faqs/combined-hormonal-birth-control-pill-patch-ring

- GoodRx. (2023). Birth Control Pill Prices. https://www.goodrx.com/birth-control

- Zhanel, G. G., Siemens, S., Slayter, K., & Mandell, L. (1999). Antibiotic and oral contraceptive drug interactions: Is there a need for concern?. Canadian Journal of Infectious Diseases, 10(6), 429-433. https://doi.org/10.1155/1999/539376

- Chou, R., McDonagh, M. S., Nakamoto, E., & Griffin, J. (2011). Analgesics for Osteoarthritis: An Update of the 2006 Comparative Effectiveness Review. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (US). https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK65646/

- GoodRx. (2023). Ibuprofen Prices. https://www.goodrx.com/ibuprofen

- Moore, N., Pollack, C., & Butkerait, P. (2015). Adverse drug reactions and drug–drug interactions with over-the-counter NSAIDs. Therapeutics and Clinical Risk Management, 11, 1061-1075. https://doi.org/10.2147/TCRM.S79135

- Ulrich, U., Taymaa, N., Rossmanith, W., Machnicki, M., Cutolo, M., Schultze-Mosgau, M. H., & Huirne, J. (2023). GnRH Agonists and Antagonists in Benign Gynecological Disorders. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 24(9), 7852. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms24097852

- GoodRx. (2023). Leuprolide Prices. https://www.goodrx.com/leuprolide

- The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. (2021). Progestin-Only Hormonal Birth Control: Pill and Injection. https://www.acog.org/womens-health/faqs/progestin-only-hormonal-birth-control-pill-and-injection

- GoodRx. (2023). Medroxyprogesterone Prices. https://www.goodrx.com/medroxyprogesterone

- Zane, L. T., Leyden, W. A., Marqueling, A. L., & Manos, M. M. (2006). A population-based analysis of laboratory abnormalities during isotretinoin therapy for acne vulgaris. Archives of dermatology, 142(8), 1016-1022. https://doi.org/10.1001/archderm.142.8.1016

- National Cancer Institute. (2023). Tamoxifen. https://www.cancer.gov/about-cancer/treatment/drugs/tamoxifencitrate

- GoodRx. (2023). Tamoxifen Prices. https://www.goodrx.com/tamoxifen

- Sideras, K., Ingle, J. N., Ames, M. M., Loprinzi, C. L., Mrazek, D. P., Black, J. L., … & Goetz, M. P. (2010). Coprescription of tamoxifen and medications that inhibit CYP2D6. Journal of Clinical Oncology, 28(16), 2768-2776. https://doi.org/10.1200/JCO.2009.23.8931

- Buttram, V. C., & Reiter, R. C. (1981). Uterine leiomyomata: etiology, symptomatology, and management. Fertility and Sterility, 36(4), 433-445. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0015-0282(16)45789-4

- Kulkarni, S., Kumarapeli, A., & Davies, C. (2021). The Use of Aromatase Inhibitors in Gynaecology. The Obstetrician & Gynaecologist, 23(2), 121-129. https://doi.org/10.1111/tog.12714

- Eisinger, S. H., Meldrum, S., Fiscella, K., le Roux, H. D., & Guzick, D. S. (2003). Low-dose mifepristone for uterine leiomyomata. Obstetrics & Gynecology, 101(2), 243-250. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0029-7844(02)02511-5

- Donnez, J., & Dolmans, M. M. (2016). Uterine fibroid management: from the present to the future. Human Reproduction Update, 22(6), 665-686. https://doi.org/10.1093/humupd/dmw023

- Sabry, M., & Al-Hendy, A. (2012). Medical treatment of uterine leiomyoma. Reproductive Sciences, 19(4), 339-353. https://doi.org/10.1177/1933719111432867

- American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. (2021). Hysterectomy. https://www.acog.org/womens-health/faqs/hysterectomy

- American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. (2021). Uterine Fibroids. https://www.acog.org/womens-health/faqs/uterine-fibroids

- American Cancer Society. (2023). Surgery for Ovarian Cancer. https://www.cancer.org/cancer/ovarian-cancer/treating/surgery.html

- American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. (2021). Management of Abnormal Cervical Cancer Screening Test Results and Cervical Cancer Precursors. https://www.acog.org/clinical/clinical-guidance/practice-bulletin/articles/2016/12/management-of-abnormal-cervical-cancer-screening-test-results-and-cervical-cancer-precursors

- American Cancer Society. (2023). Breast Biopsy. https://www.cancer.org/cancer/breast-cancer/screening-tests-and-early-detection/breast-biopsy.html

- Roshdy, E., Rajaratnam, V., Maitra, S., Sabry, M., Allah, A. S., & Al-Hendy, A. (2013). Treatment of symptomatic uterine fibroids with green tea extract: a pilot randomized controlled clinical study. International Journal of Women’s Health, 5, 477-486. https://doi.org/10.2147/IJWH.S41021

- Liang, F., Chen, R., & Cooper, E. L. (2012). Neuroendocrine mechanisms of acupuncture. Evidence-Based Complementary and Alternative Medicine, 2012, 792793. https://doi.org/10.1155/2012/792793

- Cramer, H., Lauche, R., Langhorst, J., & Dobos, G. (2012). Effectiveness of yoga for menopausal symptoms: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Evidence-Based Complementary and Alternative Medicine, 2012, 863905. https://doi.org/10.1155/2012/863905

- Chiaffarino, F., Parazzini, F., La Vecchia, C., Chatenoud, L., Di Cintio, E., & Marsico, S. (1999). Diet and uterine myomas. Obstetrics & Gynecology, 94(3), 395-398. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0029784499800350

- Frawley, H. C., Dean, S. G., Slade, S. C., & Hay-Smith, E. J. C. (2017). Is pelvic-floor muscle training a physical therapy or a behavioral therapy? A call to name and report the physical, cognitive, and behavioral elements. Physical Therapy, 97(4), 425-437. https://doi.org/10.1093/ptj/pzx006

- World Health Organization. (2020). WHO guidelines on physical activity and sedentary behaviour. https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789240015128

- U.S. Department of Health and Human Services and U.S. Department of Agriculture. (2020). Dietary Guidelines for Americans, 2020-2025. 9th Edition. https://www.dietaryguidelines.gov/sites/default/files/2020-12/Dietary_Guidelines_for_Americans_2020-2025.pdf

- Khoury, B., Sharma, M., Rush, S. E., & Fournier, C. (2015). Mindfulness-based stress reduction for healthy individuals: A meta-analysis. Journal of Psychosomatic Research, 78(6), 519-528. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpsychores.2015.03.009

- U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. (2020). Smoking Cessation: A Report of the Surgeon General. https://www.hhs.gov/sites/default/files/2020-cessation-sgr-full-report.pdf

Related articles

Made in USA