Introduction

Child behavior symptoms and complaints refer to any abnormal or concerning behaviors exhibited by children. These behaviors can range from mild to severe and may impact the child’s daily functioning and overall well-being[1]. It is important to address these symptoms and complaints promptly to ensure appropriate intervention and support for the child. This guide aims to provide a comprehensive approach to diagnosing and managing child behavior symptoms and complaints.

Codes

- ICPC-2 Code: P22 Child behavior symptom/complaint[2]

- ICD-10 Code: F91.9 Conduct disorder, unspecified[3]

Symptoms

- Aggression: The child displays frequent and intense episodes of physical or verbal aggression towards others[4].

- Hyperactivity: The child is excessively active, has difficulty sitting still, and often interrupts or intrudes on others[5].

- Inattention: The child struggles to sustain attention, is easily distracted, and has difficulty following instructions or completing tasks[5].

- Impulsivity: The child acts without thinking, has difficulty waiting their turn, and often interrupts or blurts out answers[5].

- Anxiety: The child experiences excessive worry, fear, or unease, which may manifest as restlessness, irritability, or physical symptoms such as headaches or stomachaches[6].

Causes

- Genetic factors: Certain genetic factors may contribute to the development of child behavior symptoms and complaints[7].

- Environmental factors: Adverse experiences, such as trauma, neglect, or exposure to violence, can impact a child’s behavior[8].

- Neurological factors: Differences in brain structure or function may contribute to the development of behavior symptoms and complaints[9].

- Psychological factors: Mental health conditions, such as anxiety or attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), can manifest as behavior symptoms in children[10].

Diagnostic Steps

Medical History

- Gather information about the child’s developmental history, including milestones, social interactions, and academic performance.

- Inquire about any family history of mental health conditions or behavioral issues.

- Assess for any recent life events or stressors that may be contributing to the child’s behavior symptoms[11].

Physical Examination

- Perform a thorough physical examination to rule out any underlying medical conditions that may be causing or contributing to the behavior symptoms.

- Pay particular attention to neurological signs or abnormalities that may indicate an underlying neurological disorder[12].

Laboratory Tests

- No specific laboratory tests are typically indicated for the diagnosis of child behavior symptoms. However, certain tests may be ordered to rule out other medical conditions or to assess for any underlying physiological factors contributing to the symptoms[13].

Diagnostic Imaging

- Diagnostic imaging is not typically necessary for the diagnosis of child behavior symptoms. However, in certain cases, brain imaging studies, such as MRI or CT scans, may be ordered to assess for any structural abnormalities or neurological conditions[14].

Other Tests

- Psychological assessments: These tests may be administered by a qualified mental health professional to assess the child’s cognitive abilities, emotional functioning, and behavior patterns[15].

- Behavior rating scales: These questionnaires are completed by parents, teachers, or other caregivers to provide additional information about the child’s behavior in different settings[16].

Follow-up and Patient Education

- Schedule regular follow-up appointments to monitor the child’s progress and adjust treatment interventions as needed.

- Provide education and support to the child and their caregivers regarding the nature of the behavior symptoms, treatment options, and strategies for managing and coping with the symptoms[17].

Possible Interventions

Traditional Interventions

Medications:

Top 5 drugs for Child behavior symptoms/complaints:

- Stimulant medications (e.g., Methylphenidate, Amphetamine)[18]:

- Cost: Generic versions can range from $10 to $100 per month.

- Contraindications: History of heart problems, uncontrolled high blood pressure, glaucoma.

- Side effects: Decreased appetite, trouble sleeping, increased heart rate.

- Severe side effects: Psychosis, cardiovascular events.

- Drug interactions: Monoamine oxidase inhibitors (MAOIs), certain antidepressants.

- Warning: Regular monitoring of blood pressure and heart rate required.

- Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) (e.g., Fluoxetine, Sertraline)[19]:

- Cost: Generic versions can range from $10 to $50 per month.

- Contraindications: Concurrent use of MAOIs, history of bipolar disorder.

- Side effects: Nausea, headache, sexual dysfunction.

- Severe side effects: Suicidal thoughts, serotonin syndrome.

- Drug interactions: MAOIs, certain migraine medications.

- Warning: Increased risk of suicidal thoughts in children and adolescents.

- Alpha-2 adrenergic agonists (e.g., Clonidine, Guanfacine)[20]:

- Cost: Generic versions can range from $10 to $50 per month.

- Contraindications: History of heart problems, low blood pressure.

- Side effects: Drowsiness, dry mouth, low blood pressure.

- Severe side effects: Bradycardia, rebound hypertension.

- Drug interactions: MAOIs, certain blood pressure medications.

- Warning: Regular monitoring of blood pressure and heart rate required.

- Atypical antipsychotics (e.g., Risperidone, Aripiprazole)[21]:

- Cost: Generic versions can range from $10 to $100 per month.

- Contraindications: History of heart problems, certain blood disorders.

- Side effects: Weight gain, sedation, movement disorders.

- Severe side effects: Neuroleptic malignant syndrome, metabolic changes.

- Drug interactions: Other antipsychotics, certain antidepressants.

- Warning: Increased risk of metabolic changes and movement disorders.

- Antiepileptic medications (e.g., Valproate, Lamotrigine)[22]:

- Cost: Generic versions can range from $10 to $100 per month.

- Contraindications: History of liver disease, certain blood disorders.

- Side effects: Nausea, dizziness, sedation.

- Severe side effects: Liver toxicity, Stevens-Johnson syndrome.

- Drug interactions: Oral contraceptives, certain antidepressants.

- Warning: Regular monitoring of liver function required.

Alternative Drugs:

- Non-stimulant medications (e.g., Atomoxetine): May be considered as an alternative to stimulant medications for ADHD[23].

- Bupropion: An antidepressant that may be used off-label for ADHD[24].

- Guanfacine extended-release: A long-acting form of guanfacine that may be used for ADHD[25].

- Quetiapine: An atypical antipsychotic that may be used off-label for certain behavior symptoms[26].

- Lithium: A mood stabilizer that may be used for certain behavior symptoms[27].

Behavioral Interventions:

- Cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT): A structured therapy that helps children identify and modify negative thoughts and behaviors[28].

- Parent training programs: These programs provide parents with strategies and skills to manage their child’s behavior effectively[29].

- Social skills training: Helps children develop appropriate social skills and improve their interactions with others[30].

- Applied behavior analysis (ABA): A therapy that uses positive reinforcement to teach and reinforce desired behaviors[31].

- School-based interventions: Collaborating with teachers and school staff to implement behavior management strategies and accommodations in the school setting[32].

Alternative Interventions

- Art therapy: Utilizes creative processes to help children express their emotions and improve their overall well-being. Cost: $50-$150 per session[33].

- Play therapy: Uses play as a means of communication and helps children explore and resolve their emotional difficulties. Cost: $50-$150 per session[34].

- Yoga and mindfulness: Incorporates breathing exercises, meditation, and gentle movements to promote relaxation and emotional regulation. Cost: Varies depending on the provider and location[35].

- Animal-assisted therapy: Involves interactions with trained animals to promote emotional well-being and reduce stress. Cost: Varies depending on the provider and location[36].

- Music therapy: Utilizes music and musical activities to address emotional, cognitive, and social needs. Cost: $50-$150 per session[37].

Lifestyle Interventions

- Regular exercise: Engaging in physical activities can help reduce hyperactivity, improve mood, and promote overall well-being. Cost: Varies depending on the chosen activities[38].

- Healthy diet: Providing a balanced diet rich in fruits, vegetables, whole grains, and lean proteins can support optimal brain function and behavior. Cost: Varies depending on food choices and dietary preferences[39].

- Sufficient sleep: Ensuring an adequate amount of sleep can improve attention, mood, and overall behavior. Cost: None[40].

- Stress management techniques: Teaching children relaxation techniques, such as deep breathing or mindfulness exercises, can help reduce anxiety and improve behavior. Cost: None[41].

- Consistent routines and structure: Establishing predictable routines and clear expectations can help children feel more secure and reduce behavior problems. Cost: None[42].

It is important to note that the cost ranges provided are approximate and may vary depending on the location and availability of the interventions.

Mirari Cold Plasma Alternative Intervention

Understanding Mirari Cold Plasma

- Safe and Non-Invasive Treatment: Mirari Cold Plasma is a safe and non-invasive treatment option for various skin conditions. It does not require incisions, minimizing the risk of scarring, bleeding, or tissue damage.

- Efficient Extraction of Foreign Bodies: Mirari Cold Plasma facilitates the removal of foreign bodies from the skin by degrading and dissociating organic matter, allowing easier access and extraction.

- Pain Reduction and Comfort: Mirari Cold Plasma has a local analgesic effect, providing pain relief during the treatment, making it more comfortable for the patient.

- Reduced Risk of Infection: Mirari Cold Plasma has antimicrobial properties, effectively killing bacteria and reducing the risk of infection.

- Accelerated Healing and Minimal Scarring: Mirari Cold Plasma stimulates wound healing and tissue regeneration, reducing healing time and minimizing the formation of scars.

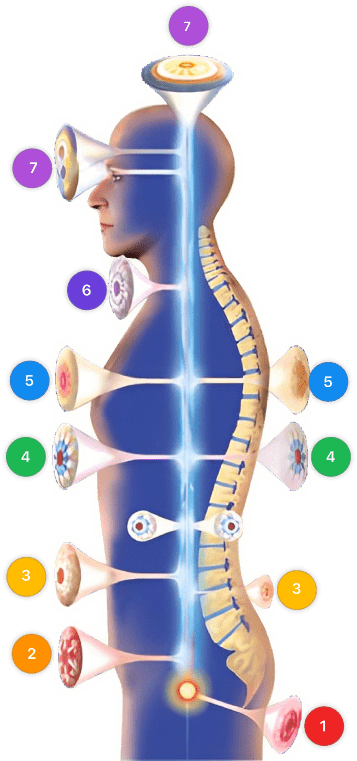

Mirari Cold Plasma Prescription

Video instructions for using Mirari Cold Plasma Device – P22 Child behavior symptom/complaint (ICD-10:F91.9)

| Mild | Moderate | Severe |

| Mode setting: 2 (Wound Healing) Location: 7 (Neuro system & ENT) Morning: 15 minutes, Evening: 15 minutes |

Mode setting: 2 (Wound Healing) Location: 7 (Neuro system & ENT) Morning: 30 minutes, Lunch: 30 minutes, Evening: 30 minutes |

Mode setting: 2 (Wound Healing) Location: 7 (Neuro system & ENT) Morning: 30 minutes, Lunch: 30 minutes, Evening: 30 minutes |

| Mode setting: 7 (Immunotherapy) Location: 1 (Sacrum) Morning: 15 minutes, Evening: 15 minutes |

Mode setting: 7 (Immunotherapy) Location: 1 (Sacrum) Morning: 30 minutes, Lunch: 30 minutes, Evening: 30 minutes |

Mode setting: 7 (Immunotherapy) Location: 1 (Sacrum) Morning: 30 minutes, Lunch: 30 minutes, Evening: 30 minutes |

| Mode setting: 7 (Immunotherapy) Location: 1 (Sacrum) Morning: 15 minutes, Evening: 15 minutes |

Mode setting: 7 (Immunotherapy) Location: 1 (Sacrum) Morning: 30 minutes, Lunch: 30 minutes, Evening: 30 minutes |

Mode setting: 7 (Immunotherapy) Location: 1 (Sacrum) Morning: 30 minutes, Lunch: 30 minutes, Evening: 30 minutes |

| Total Morning: 45 minutes approx. $7.50 USD, Evening: 45 minutes approx. $7.50 USD |

Total Morning: 90 minutes approx. $15 USD, Lunch: 90 minutes approx. $15 USD, Evening: 90 minutes approx. $15 USD, |

Total Morning: 90 minutes approx. $15 USD, Lunch: 90 minutes approx. $15 USD, Evening: 90 minutes approx. $15 USD, |

| Usual treatment for 7-60 days approx. $105 USD – $900 USD | Usual treatment for 6-8 weeks approx. $1,890 USD – $2,520 USD |

Usual treatment for 3-6 months approx. $4,050 USD – $8,100 USD

|

|

|

Use the Mirari Cold Plasma device to treat Child behavior symptom/complaint effectively.

WARNING: MIRARI COLD PLASMA IS DESIGNED FOR THE HUMAN BODY WITHOUT ANY ARTIFICIAL OR THIRD PARTY PRODUCTS. USE OF OTHER PRODUCTS IN COMBINATION WITH MIRARI COLD PLASMA MAY CAUSE UNPREDICTABLE EFFECTS, HARM OR INJURY. PLEASE CONSULT A MEDICAL PROFESSIONAL BEFORE COMBINING ANY OTHER PRODUCTS WITH USE OF MIRARI.

Step 1: Cleanse the Skin

- Start by cleaning the affected area of the skin with a gentle cleanser or mild soap and water. Gently pat the area dry with a clean towel.

Step 2: Prepare the Mirari Cold Plasma device

- Ensure that the Mirari Cold Plasma device is fully charged or has fresh batteries as per the manufacturer’s instructions. Make sure the device is clean and in good working condition.

- Switch on the Mirari device using the power button or by following the specific instructions provided with the device.

- Some Mirari devices may have adjustable settings for intensity or treatment duration. Follow the manufacturer’s instructions to select the appropriate settings based on your needs and the recommended guidelines.

Step 3: Apply the Device

- Place the Mirari device in direct contact with the affected area of the skin. Gently glide or hold the device over the skin surface, ensuring even coverage of the area experiencing.

- Slowly move the Mirari device in a circular motion or follow a specific pattern as indicated in the user manual. This helps ensure thorough treatment coverage.

Step 4: Monitor and Assess:

- Keep track of your progress and evaluate the effectiveness of the Mirari device in managing your Child behavior symptom/complaint. If you have any concerns or notice any adverse reactions, consult with your health care professional.

Note

This guide is for informational purposes only and should not replace the advice of a medical professional. Always consult with your healthcare provider or a qualified medical professional for personal advice, diagnosis, or treatment. Do not solely rely on the information presented here for decisions about your health. Use of this information is at your own risk. The authors of this guide, nor any associated entities or platforms, are not responsible for any potential adverse effects or outcomes based on the content.

Mirari Cold Plasma System Disclaimer

- Purpose: The Mirari Cold Plasma System is a Class 2 medical device designed for use by trained healthcare professionals. It is registered for use in Thailand and Vietnam. It is not intended for use outside of these locations.

- Informational Use: The content and information provided with the device are for educational and informational purposes only. They are not a substitute for professional medical advice or care.

- Variable Outcomes: While the device is approved for specific uses, individual outcomes can differ. We do not assert or guarantee specific medical outcomes.

- Consultation: Prior to utilizing the device or making decisions based on its content, it is essential to consult with a Certified Mirari Tele-Therapist and your medical healthcare provider regarding specific protocols.

- Liability: By using this device, users are acknowledging and accepting all potential risks. Neither the manufacturer nor the distributor will be held accountable for any adverse reactions, injuries, or damages stemming from its use.

- Geographical Availability: This device has received approval for designated purposes by the Thai and Vietnam FDA. As of now, outside of Thailand and Vietnam, the Mirari Cold Plasma System is not available for purchase or use.

References

- Ogundele, M. O. (2018). Behavioural and emotional disorders in childhood: A brief overview for paediatricians. World Journal of Clinical Pediatrics, 7(1), 9-26. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5803568/

- World Health Organization. (2023). ICPC-2: International Classification of Primary Care, Second edition. WHO. https://www.who.int/standards/classifications/other-classifications/international-classification-of-primary-care

- World Health Organization. (2019). ICD-10: International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems 10th Revision. WHO. https://icd.who.int/browse10/2019/en#/F91.9

- Zahrt, D. M., & Melzer-Lange, M. D. (2011). Aggressive Behavior in Children and Adolescents. Pediatrics in Review, 32(8), 325-332. https://publications.aap.org/pediatricsinreview/article-abstract/32/8/325/32638/Aggressive-Behavior-in-Children-and-Adolescents?redirectedFrom=fulltext

- American Psychiatric Association. (2022). What is ADHD? https://www.psychiatry.org/patients-families/adhd/what-is-adhd

- Anxiety and Depression Association of America. (2023). Childhood Anxiety Disorders. ADAA. https://adaa.org/living-with-anxiety/children/childhood-anxiety-disorders

- Faraone, S. V., & Larsson, H. (2019). Genetics of attention deficit hyperactivity disorder. Molecular Psychiatry, 24(4), 562-575. https://www.nature.com/articles/s41380-018-0070-0

- McLaughlin, K. A., Green, J. G., Gruber, M. J., Sampson, N. A., Zaslavsky, A. M., & Kessler, R. C. (2010). Childhood adversities and adult psychiatric disorders in the national comorbidity survey replication II: associations with persistence of DSM-IV disorders. Archives of General Psychiatry, 67(2), 124-132. https://jamanetwork.com/journals/jamapsychiatry/fullarticle/210584

- Shaw, P., Eckstrand, K., Sharp, W., Blumenthal, J., Lerch, J. P., Greenstein, D., … & Rapoport, J. L. (2007). Attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder is characterized by a delay in cortical maturation. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 104(49), 19649-19654. https://www.pnas.org/doi/full/10.1073/pnas.0707741104

- American Psychiatric Association. (2013). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (5th ed.). Arlington, VA: American Psychiatric Publishing. https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.books.9780890425596

- Boyle, C. A., Boulet, S., Schieve, L. A., Cohen, R. A., Blumberg, S. J., Yeargin-Allsopp, M., … & Kogan, M. D. (2011). Trends in the prevalence of developmental disabilities in US children, 1997–2008. Pediatrics, 127(6), 1034-1042. https://publications.aap.org/pediatrics/article/127/6/1034/28689/Trends-in-the-Prevalence-of-Developmental

- American Academy of Pediatrics. (2019). Clinical Practice Guideline for the Diagnosis, Evaluation, and Treatment of Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder in Children and Adolescents. Pediatrics, 144(4), e20192528. https://publications.aap.org/pediatrics/article/144/4/e20192528/81590/Clinical-Practice-Guideline-for-the-Diagnosis

- Subcommittee on Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder, Steering Committee on Quality Improvement and Management. (2011). ADHD: Clinical Practice Guideline for the Diagnosis, Evaluation, and Treatment of Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder in Children and Adolescents. Pediatrics, 128(5), 1007-1022. https://publications.aap.org/pediatrics/article/128/5/1007/30922/ADHD-Clinical-Practice-Guideline-for-the-Diagnosis

- Weyandt, L., Swentosky, A., & Gudmundsdottir, B. G. (2013). Neuroimaging and ADHD: fMRI, PET, DTI findings, and methodological limitations. Developmental neuropsychology, 38(4), 211-225. https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1080/87565641.2013.783833

- Achenbach, T. M., & Rescorla, L. A. (2001). Manual for the ASEBA School-Age Forms & Profiles. Burlington, VT: University of Vermont, Research Center for Children, Youth, & Families. https://aseba.org/school-age/

- Conners, C. K., Pitkanen, J., & Rzepa, S. R. (2011). Conners 3rd Edition (Conners 3; Conners 2008). In J. S. Kreutzer, J. DeLuca, & B. Caplan (Eds.), Encyclopedia of Clinical Neuropsychology (pp. 675-678). New York, NY: Springer. https://storefront.mhs.com/collections/conners-cpt-3

- Pelham, W. E., & Fabiano, G. A. (2008). Evidence-based psychosocial treatments for attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Journal of Clinical Child & Adolescent Psychology, 37(1), 184-214. https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1080/15374410701818681

- Cortese, S., Adamo, N., Del Giovane, C., Mohr-Jensen, C., Hayes, A. J., Carucci, S., … & Cipriani, A. (2018). Comparative efficacy and tolerability of medications for attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder in children, adolescents, and adults: a systematic review and network meta-analysis. The Lancet Psychiatry, 5(9), 727-738. https://www.thelancet.com/journals/lanpsy/article/PIIS2215-0366(18)30269-4/fulltext

- Cipriani, A., Zhou, X., Del Giovane, C., Hetrick, S. E., Qin, B., Whittington, C., … & Xie, P. (2016). Comparative efficacy and tolerability of antidepressants for major depressive disorder in children and adolescents: a network meta-analysis. The Lancet, 388(10047), 881-890. https://www.thelancet.com/journals/lancet/article/PIIS0140-6736(16)30385-3/fulltext

- Ruiz-Goikoetxea, M., Cortese, S., Aznarez-Sanado, M., Magallón, S., Alvarez Zallo, N., Luis, E. O., … & Arrondo, G. (2018). Risk of unintentional injuries in children and adolescents with ADHD and the impact of ADHD medications: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Neuroscience & Biobehavioral Reviews, 84, 63-71. https://www.jaacap.org/article/S0890-8567(13)00818-6/abstract

- Loy, J. H., Merry, S. N., Hetrick, S. E., & Stasiak, K. (2017). Atypical antipsychotics for disruptive behaviour disorders in children and youths. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, (8). https://www.cochranelibrary.com/cdsr/doi/10.1002/14651858.CD008559.pub3/full

- Perucca, E. (2002). Pharmacological and therapeutic properties of valproate. CNS drugs, 16(10), 695-714. https://link.springer.com/article/10.2165/00023210-200216100-00004

- Garnock-Jones, K. P., & Keating, G. M. (2009). Atomoxetine: a review of its use in attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder in children and adolescents. Pediatric Drugs, 11(3), 203-226. https://link.springer.com/article/10.2165/00148581-200911030-00005

- Maneeton, N., Maneeton, B., Intaprasert, S., & Woottiluk, P. (2014). A systematic review of randomized controlled trials of bupropion versus methylphenidate in the treatment of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Neuropsychiatric Disease and Treatment, 10, 1439-1449. https://doi.org/10.2147/ndt.s62714

- Biederman, J., Melmed, R. D., Patel, A., McBurnett, K., Konow, J., Lyne, A., & Scherer, N. (2008). A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study of guanfacine extended release in children and adolescents with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Pediatrics, 121(1), e73-e84. https://doi.org/10.1097/chi.0b013e318191769e

- Maglione, M., Maher, A. R., Hu, J., Wang, Z., Shanman, R., Shekelle, P. G., … & Perry, T. (2011). Off-label use of atypical antipsychotics: an update. Comparative Effectiveness Reviews, No. 43. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK66081/

- Findling, R. L., Gracious, B. L., McNamara, N. K., Youngstrom, E. A., Demeter, C. A., Branicky, L. A., & Calabrese, J. R. (2001). Rapid, continuous cycling and psychiatric co-morbidity in pediatric bipolar I disorder. Bipolar Disorders, 3(4), 202-210. https://doi.org/10.1034/j.1399-5618.2001.030405.x

- Kendall, P. C., & Hedtke, K. A. (2006). Cognitive-Behavioral Therapy for Anxious Children: Therapist Manual (3rd ed.). Workbook Publishing. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/308140280_Cognitive-Behavioral_Therapy_for_Anxious_Children_Therapist_Manual

- Sanders, M. R., Kirby, J. N., Tellegen, C. L., & Day, J. J. (2014). The Triple P-Positive Parenting Program: A systematic review and meta-analysis of a multi-level system of parenting support. Clinical Psychology Review, 34(4), 337-357. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cpr.2014.04.003

- Reichow, B., Steiner, A. M., & Volkmar, F. (2013). Social skills groups for people aged 6 to 21 with autism spectrum disorders (ASD). Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, (7). https://www.cochranelibrary.com/cdsr/doi/10.1002/14651858.CD008511.pub2/full

- Reichow, B., Hume, K., Barton, E. E., & Boyd, B. A. (2018). Early intensive behavioral intervention (EIBI) for young children with autism spectrum disorders (ASD). Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, (5). https://www.cochranelibrary.com/cdsr/doi/10.1002/14651858.CD009260.pub3/full

- DuPaul, G. J., Eckert, T. L., & Vilardo, B. (2012). The effects of school-based interventions for attention deficit hyperactivity disorder: A meta-analysis 1996-2010. School Psychology Review, 41(4), 387-412. https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1080/02796015.2012.12087496

- Regev, D., & Cohen-Yatziv, L. (2018). Effectiveness of art therapy with adult clients in 2018—What progress has been made?. Frontiers in Psychology, 9, 1531. https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fpsyg.2018.01531/full

- Lin, Y. W., & Bratton, S. C. (2015). A meta‐analytic review of child‐centered play therapy approaches. Journal of Counseling & Development, 93(1), 45-58. https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/abs/10.1002/j.1556-6676.2015.00180.x

- Chimiklis, A. L., Dahl, V., Spears, A. P., Goss, K., Fogarty, K., & Chacko, A. (2018). Yoga, mindfulness, and meditation interventions for youth with ADHD: Systematic review and meta-analysis. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 27(10), 3155-3168. https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s10826-018-1148-7

- Nimer, J., & Lundahl, B. (2007). Animal-assisted therapy: A meta-analysis. Anthrozoös, 20(3), 225-238. https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.2752/089279307X224773

- Gold, C., Wigram, T., & Elefant, C. (2006). Music therapy for autistic spectrum disorder. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, (2). https://www.cochranelibrary.com/cdsr/doi/10.1002/14651858.CD004381.pub2/full

- Cerrillo‐Urbina, A. J., García‐Hermoso, A., Sánchez‐López, M., Pardo‐Guijarro, M. J., Santos Gómez, J. L., & Martínez‐Vizcaíno, V. (2015). The effects of physical exercise in children with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder: A systematic review and meta‐analysis of randomized control trials. Child: Care, Health and Development, 41(6), 779-788. https://doi.org/10.1080/15377903.2016.1265622

- Nigg, J. T., & Holton, K. (2014). Restriction and elimination diets in ADHD treatment. Child and Adolescent Psychiatric Clinics of North America, 23(4), 937-953. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4322780/

- Gruber, R., Wiebe, S., Montecalvo, L., Brunetti, B., Amsel, R., & Carrier, J. (2011). Impact of sleep restriction on neurobehavioral functioning of children with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder. Sleep, 34(3), 315-323. https://doi.org/10.1093/sleep/34.3.315

- Semple, R. J., Lee, J., Rosa, D., & Miller, L. F. (2010). A randomized trial of mindfulness-based cognitive therapy for children: Promoting mindful attention to enhance social-emotional resiliency in children. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 19(2), 218-229. https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s10826-009-9301-y

- Chronis, A. M., Chacko, A., Fabiano, G. A., Wymbs, B. T., & Pelham Jr, W. E. (2004). Enhancements to the behavioral parent training paradigm for families of children with ADHD: Review and future directions. Clinical Child and Family Psychology Review, 7(1), 1-27. https://link.springer.com/article/10.1023/B:CCFP.0000020190.60808.a4

Related articles

Made in USA